August 21, 2019

Access to electricity – at any cost?

Sustainable Development Goal 7 aims to ensure access to affordable, reliable, sustainable and modern energy for all by 2030. Some progress has been made but Sub-Saharan Africa remains a challenge.

International Energy Agency recently published data showing that, for the first time in modern history, the global population without access to electricity is below 1 billion. Many of the new connections have been made in India where the government’s electrification plan to cover all villages is bearing fruit.

However, in Sub-Saharan Africa the progress has been less impressive. The IEA estimates that the great majority of households with no access to electricity will continue to be found in Sub-Saharan Africa also in the future.

In February this year, The Economist published an article that caused some stir by claiming that electricity does not raise people from poverty, citing research to support the argument. The article also claims that from national economy point of view, it is not necessarily smart for governments to offer expensive connections to rural poor, again referring to research.

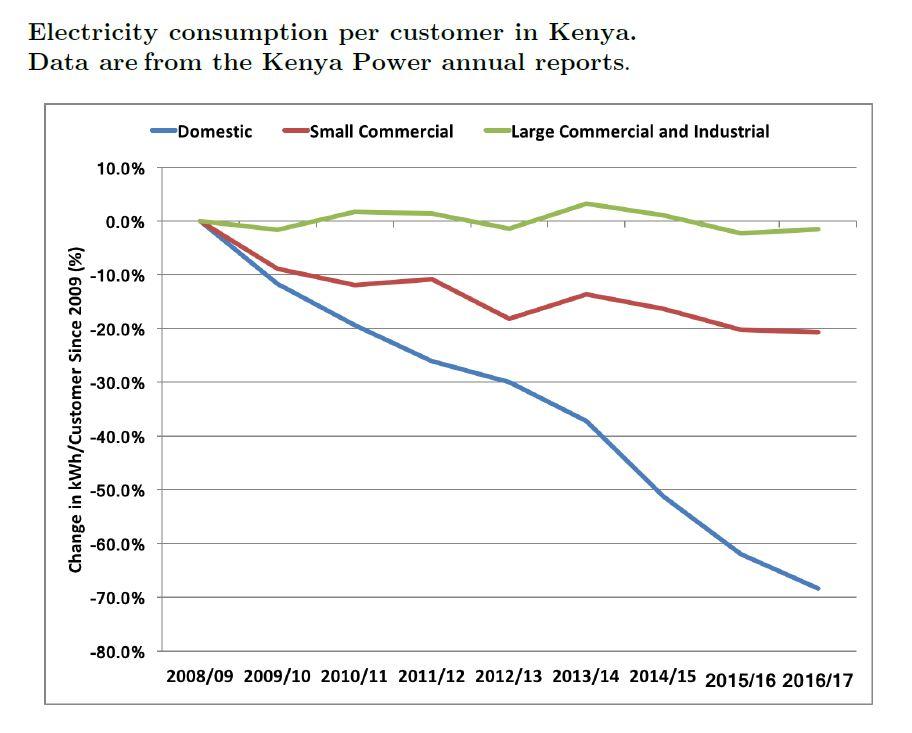

For example, in Kenya the government has decisively increased electricity generation and connections, and access to electricity has increased from 20% to over 50% in the last ten years and continues to increase. However, at the same time the average electricity consumption per domestic household has shrunk by almost 70%.

Source: Taneja (2018) with data from Kenya Power

In Kenya, the cost of a new connection to the government is estimated to be around EUR 1,500. The consumption in the new connections is not enough to cover this cost, consequently, increasing access has created losses to the national utility. 1) Electricity in Africa is more expensive than anywhere else in the world, yet there are only two countries (Uganda and Seychelles) where utilities can cover both their operating and capital expenses. 2)

A recent study by the World Bank argues that the main problem in increasing access to electricity in Africa is poverty, not insufficient generation. 3) It has also been established that bringing grid to rural areas does not automatically bring wealth. For poorer and rural households cheaper and more flexible mini-grids and household solar systems are better options for electricity access.

Wonderful solar home systems?

Popularity of the off-grid solar home systems 4) (SHS) has increased rapidly in the past ten years. GOGLA 5), the voice of the off-grid solar energy industry, estimates that over 40 million solar lanterns or SHS have been sold in the 2010s. Over 90% of the sold units are either lanterns or smaller systems and only 10% are SHSs that have enough capacity to power multiple lights and appliances. 6)

Off-grid SHSs and solar lanterns have also become one of the development practitioners’ and financiers’ favourite products with high expectations to solve multiple development challenges. Solar systems and lanterns are – at least in theory – cheaper, safer, cleaner, environmentally friendlier and have more lighting capacity than the widely used candles and kerosene lanterns.

Several studies have been conducted on the impacts of the solar lanterns and smaller systems. The studies find no transformative poverty reduction impact and other findings are ambiguous. Solar lanterns reduce the use of kerosene lamps and are slightly cheaper than candles and kerosene, but they cannot be shown to increase economic activity or increase the time children use for homework or improve learning results. However, the reduction in kerosene use is a significant result in it-self. 7)

Another challenge is that selling solar lanterns and SHSs to the poorest segment of society has proven to be financially non-sustainable. 8)

There are, however, very few studies on the impact of larger, over 11-watt, solar home systems. To fill this gap, GOGLA commissioned a research covering 2,300 households with bigger SHSs. To capture the impact, the change that the SHS brought, the households were interviewed first at the time of purchase and then some months later. The interviews were conducted in Kenya, Rwanda, Uganda, Tanzania and Mozambique. 9)

Who buys SHSs and why?

Based on the research, the typical buyer is a 37-year-old man, who lives in rural areas with his wife and three children. However, the bigger the system purchased, the more likely it is that the buyer lives in a city or around a city.

Only one third of the buyers were farmers, which is a lot less than the share of farmers of the total population. Another third of buyers were entrepreneurs, and permanent jobholders comprised 20% of the buyers. In summary, compared to national averages, a typical SHS buyer is more likely to live in (peri-) urban areas and gain livelihood from something else than agriculture.

The main reason for purchasing the SHS was to obtain more reliable lighting than what was provided by kerosene, torches and candles. The other big reasons were ability to charge mobile phone and to watch TV. Only 5% bought the SHS in order to save money. In fact, especially if the SHS was acquired with pay-as-you-go payment method, the SHSs increased energy costs by 50%, though this is still less than a euro per week.

Improved quality of life

First and foremost, the study found that despite increased costs, 96% of the buyers were happy with the SHS. The stated reasons matched with the reasons why the SHS was purchased.

With the SHS, house lights are on longer and they burn brighter 10). Only one percent of households continued using kerosene as the main source lighting while during the time of purchase, the share was 40%. This shift brings significant health benefits. In a related study in rural Kenya, it was found that replacing kerosene lanterns with solar lights reduced harmful (PM 2.5) particles by 61% in living rooms and 79% in children’s bedrooms. 11)

Furthermore, 93% of the households did not have to pay for mobile charging anymore and 89% said that they were able to use their mobile phones more.

Approximately 60% of the buyers were able to increase their economic activities. For many the business was mobile charging or showing TV for a fee, but many used SHSs also in shops and restaurants, where the financial benefits of the SHS were 10 times higher than in the phone charging business.

According to the study, the SHS increased household incomes by 35 dollars a month on average. This is many times more than the increased costs. Consequently, ¾ of the households had more money to spend on children’s education and food.

The above benefits are all very important. However, the most significant change the SHSs brought was the improvement in people’s quality of life. Over 90% said that their lives had improved because there was more light, mobiles were always charged and no-one had to travel to buy kerosene or to charge phones. Increased lighting increased also security at home, and 90% said the health of the family members had improved. And yes, kids could do their homework for longer time.

Smart planning and solutions are needed

Electricity consumption and wealth are correlated, but the causality between the two is ambiguous. There is, however, clear evidence that electricity improves quality of life. For many households in Africa, solar lanterns are the best way to bring basic lighting. Equally, for many households, Solar Home Systems are the most viable systems as the main and only source of electricity. It is also clear that Solar Home Systems are not used by the poorest and rural households alone. They are also used in grid-connected households as backup systems or to replace and complement the polluting and noisy diesel-generators 12).

In May this year Financial Times published a story – “A cautionary tale for impact investors” – about Mobisol, Finnfund’s investee company, that had filed for self-administered insolvency 13). While going through restructuring, business operations continue to full extent and Mobisol remains one of the leading companies offering Solar Home Systems for poor customers in East Africa.

To meet the SDG targets, more conscientious planning is required with an understanding that different solutions are required for different customers. It is clear that relying purely on grid electricity that is too expensive for governments and consumers alike cannot be the sole answer. Mini-grids and off-grid solutions may solve part of the problem as well as Solar Home Systems. But unfortunately, there are millions of people for whom even the cheapest solar systems may be too expensive.

To maximise development impact of power investments, Finnfund strives to better understand what the cost and consumption thresholds are, for what type of connections, and for what type of households.

Juho Uusihakala

Senior Development Impact Adviser

Finnfund

1) Taneja, Jay (2018): If you build it, will they consume? Key challenges for universal, reliable and low-cost electricity delivery in Kenya. Centre for Global Development Working Paper 491, July 2018.

2) Kojima, M and Trimble C (2016): Making power affordable for Africa and viable for its utilities. World Bank.

3) Blimbo, Moussa P., and Malcolm Cosgrove-Davies (2019): Electricity Access in Sub-Saharan Africa: Uptake, Reliability and Complementary Factors for Economic Impact. Africa Development Forum Series, World Bank.

4) Household solar home systems have capacity of at least 11 watts and generate enough electricity for multiple lamps and mobile charging. Larger systems are sufficient for TV and other applicance, even fridge.

6) GOGLA (2018): Off-grid solar market trends report 2018, https://www.gogla.org/sites/default/files/resource_docs/2018_mtr_full_report_low-res_2018.01.15_final.pdf

7) E.g. Rom et al (2017): The economic impact of solar lightning. Results from a randomised field experiment in rural Kenya tai Grimm et al (2016): A first step up the energy ladder? Low cost solar kits and household welfare in rural Rwanda.

8) IEG (2016); GOGLA (2018),

9) GOGLA (2018): Powering opportunity. The Economic Impact of Off-Grid Solar.

10) A 60-watt led light creates 800 lumens which 60 times more than kerosene lantern!

11) Lam et al (2018): Exposure reductions associated with introduction of solar lamps to kerosene lamp-using households in Busia County, Kenya. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/320390384_Exposure_reductions_associated_with_introduction_of_solar_lamps_to_kerosene_lamp-using_households_in_Busia_County_Kenya

12) Ben Leo, Jared Kalow, and Todd Moss (2018): What Can We Learn about Energy Access and Demand from Mobile-Phone Survey? Nine Findings from Twelve African Countries. Centre for Global Development.

13) https://www.ft.com/content/8832bffc-f319-36fa-a720-fadaaf86e4f4